Wright-Giemsa-stained peripheral blood smear of Anaplasma phagocytophilum

Life Cycle & Transmission

Anaplasmosis is caused by the bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum. People can become infected with the bacteria when they are bitten by the deer tick (Ixodes scapularis). Unlike Lyme disease, ticks can be attached for as little as 4-24 hours before transmitting the bacteria to its human host (Bakken and Dumler 2015). For more information on disease transmission and the life cycle of deer ticks, please see the “Tick Ecology” section.

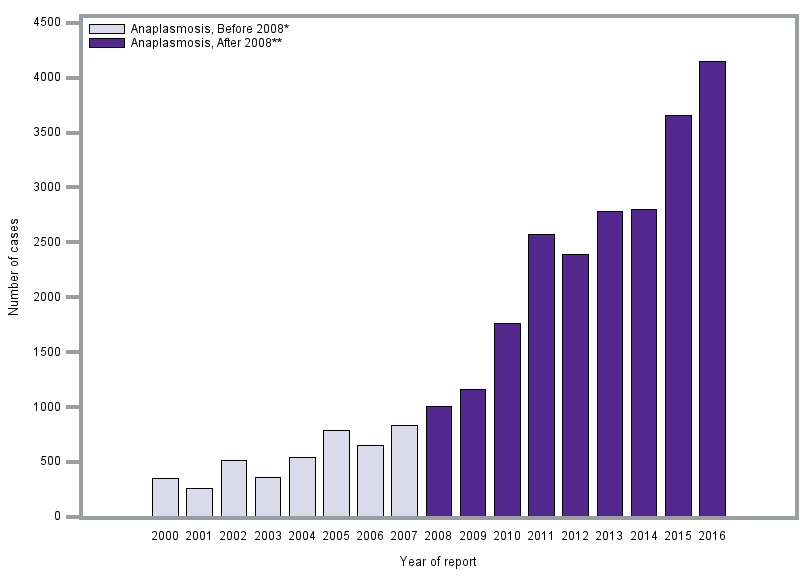

Who Gets Anaplasmosis & Where?

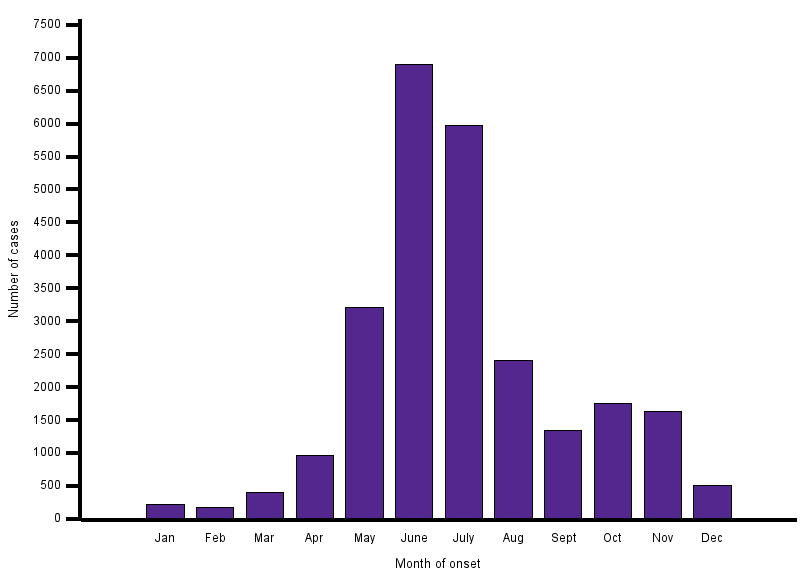

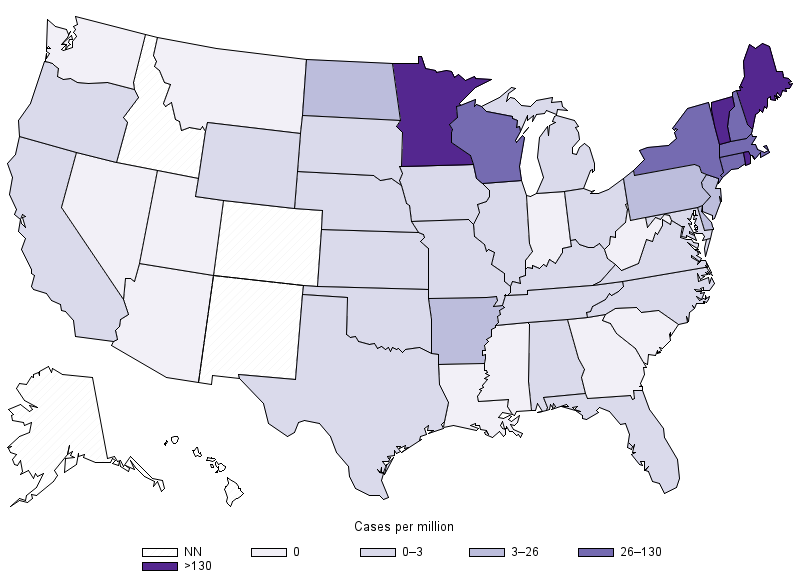

In the U.S., anaplasmosis was first recognized in six patients from northern Minnesota and Wisconsin presenting with acute febrile illnesses between 1990 and 1993. It was previously known as human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE), when Anaplasma phagocytophilum was referred to as Ehrlichia equi and Ehrlichia phagocytophilum. However, a taxonomic change in 2001 identified that this organism belonged to the genus Anaplasma, and resulted in a change in the name of the disease to anaplasmosis (CDC 2018). Anaplasmosis occurs most frequently in the Upper Midwest and Northeast regions of the U.S. The number of reported cases is highest among males and people over 40 years of age, as well as people who have a high level of exposure to tick habitats, such as campers, hikers, and outdoor workers. The majority of illnesses are reported in late spring/early summer, when nymphs are most active.

Symptoms

Signs and symptoms usually begin 1-2 weeks after the bite of an infected tick. Early stage symptoms (days 1-5) can include:

Severe headache

Fever and chills

Muscle aches

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite

Late stage symptoms can develop if treatment is delayed and include:

Respiratory failure

Bleeding problems

Organ failure

Death

Diagnosis

Blood tests are used to detect the presence of antibodies to anaplasmosis bacteria.

Treatment

Antibiotics are effective at clearing an infection. Typical treatment involves 2-3 weeks of doxycycline.

For information on prevention, please see the “Tick Ecology” section.

Sources

CDC 2018 (“Anaplasmosis”): https://www.cdc.gov/anaplasmosis/index.html

Bakken and Dumler, 2015. (“Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis”): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4441757/?report=classic

For additional reading, please visit the “Resources” tab.